Bad Boy

By Freya Rock

Edited by Leni Wascher

"Although his eyes are glaring straight ahead, I can't help but feel that he's looking past me."

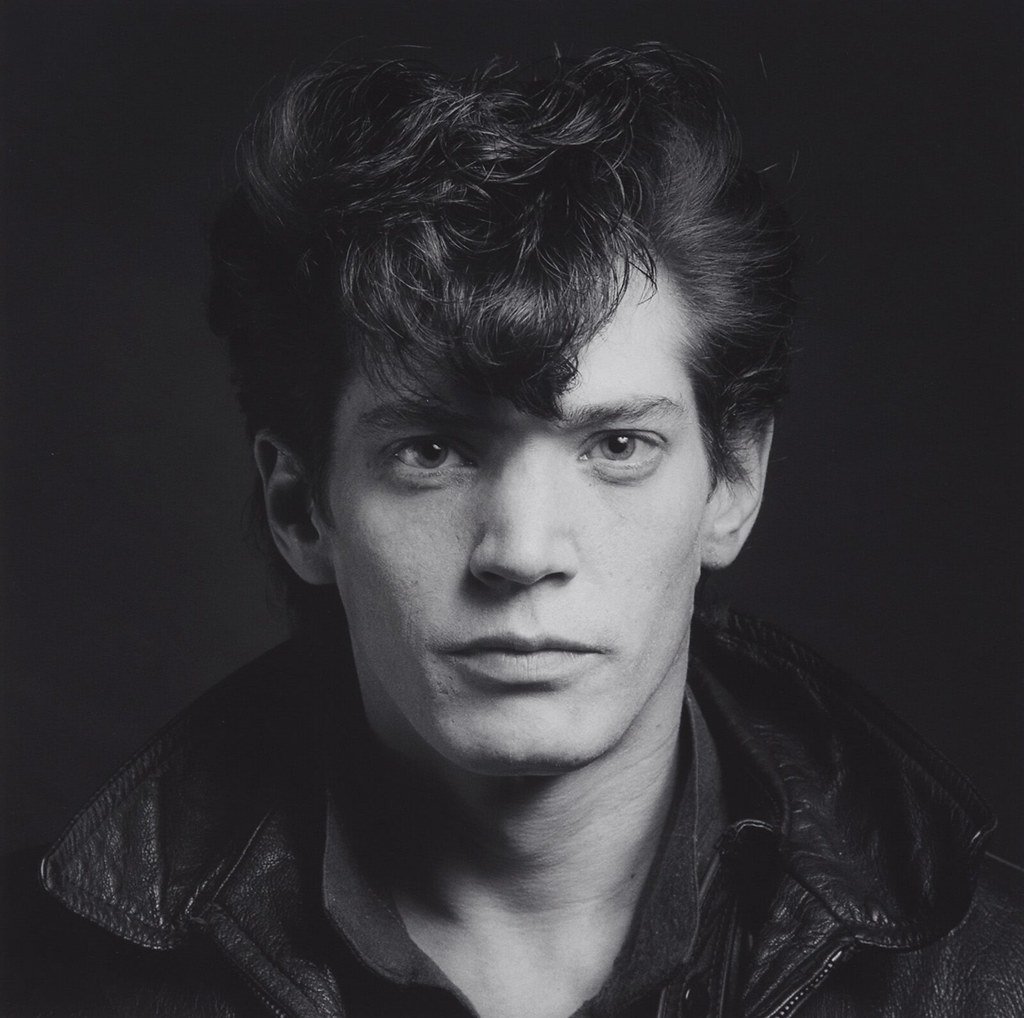

When I turned the corner and looked at the wall and spotted a monotone self-portrait of a pale man in a stark black leather jacket with slicked-back dark hair, my first instinct was to make a crack at my best friend. (She has a thing for bad boys). As I get closer to the square self-portrait I recognize this figure, Robert Mapplethorpe. This is the man that got both my brother and I into black-and-white film. He's probably cost my family a couple of hundred dollars. I'm thinking that my dad might resent this man more than I love him.

I first became familiar with his works through Patti Smith. Her work Just Kids, dedicated to Robert, is the only piece of literature I've ever cried while reading. This is the first work of his I've seen in person. The 1980s self-portrait alludes to the 1950s greaser style. Roberts sported a grey popped collared shirt, coiffed black; owl-like hair, and a thick heavy leather jacket against a solid grey background. Greasers were known for their rough exterior. Although the greaser style embodies a harsh form of masculinity, greasers did not shy away from emotional expression, not unlike Robert.

Self-portraits of artists are always deeply tied to the identity of the artist. In this photograph, we are greeted with one of Mapplethorpe's many egos. Robert is stern, facing the camera, cocky, self-assured. We see him portray himself as an object of desire. Although his eyes are glaring straight ahead, I can't help but feel that he's looking past me. I cannot hold his gaze– he's unattainable and maybe that's why I like him even more. Robert is aware he is under the self-imposed spectacle, embracing it, offering himself to the viewer’s gaze.

In many of Robert's works, faces are not shown, yet here he is, all exposed. I’m sitting, staring at a man in a leather jacket and the only word I can think of is vulnerability. Robert utilizes high-contrast imaging as a way of highlighting his self-vulnerability and juxtaposing it with his “bad boy” persona. The photo is oddly intimate. You can feel Roberts's presence in the room, even as you walk through the museum; Mapplethorpe is there.

Mapplethorpe utilizes lighting to give his face a sculptural look. His jawline and cheekbones are accentuated. He further illustrates the face with a tightly packed composition and a simple grey-tone background. We don’t know Robert and never will, yet we get to know the way his earlobe is curved, and how his eyebrow crinkles.

The photograph is framed in glass, and as I stood at eye level with Mapplethorpe's proportional head, my reflection in the glass became him; or more I became him. Suddenly I stood in a shitty New York apartment, embracing my youth, sweating my art. I'm sitting there thinking that maybe I miss New York and I can't help but think that it's time to return home. And this although I know the man is dead, I've even read a 300-page book about it. I swear for a second, as I sat staring at his tilted stare, he became real. I believed for just a moment, that if I just kept staring long enough he would be standing right in front of me, maybe just outta reach.

So maybe we're into “bad boys” because they represent all the desires we can’t have. Mapplethorpe uses his self-portrait to play with identity and desire. So maybe I like Robert Mapplethorpe for the same reason we like this idea of “bad boys”; because they're just out of reach.